Soft things in a Hard Year

Soft Things in a Hard Year: Lao Tzu, Night Work and Ordinary Men

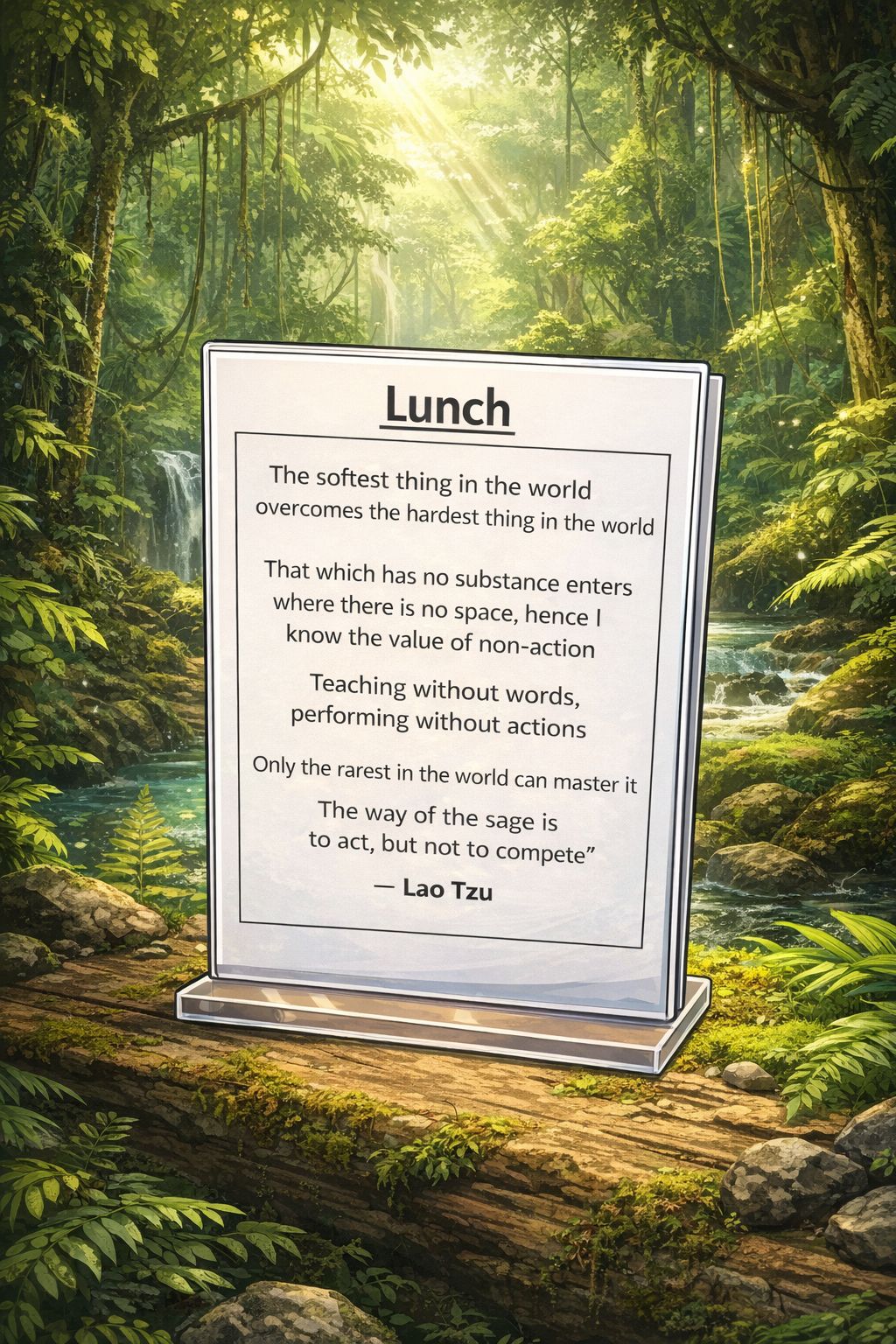

New Year always feels a bit like standing in a forest clearing at dawn. The old year is still clinging to the trees, the new one hasn’t quite arrived, and you’re somewhere in the middle holding a takeaway coffee and wondering how you’ve survived another round. This time, as I sat with that familiar mixture of fatigue, gratitude and quiet dread, I kept coming back to one small sign a quote from Lao Tzu about how “the softest thing in the world overcomes the hardest thing in the world.” Every time I look at it I think: that’s spiritual wisdom and also a surprisingly accurate description of a tired man in night shifts slowly paying off council tax.

A brief wander with Lao Tzu

Lao Tzu is more legend than biography. Tradition says he was an older contemporary of Confucius, a keeper of archives who, disillusioned with the noise of public life, rode off toward the western mountains. At a border pass, he was asked to write down his teaching before disappearing into obscurity, leaving behind what became the Tao Te Ching, a slim book that somehow manages to be both baffling and quietly life-altering (Lao Tzu, trans. Lau, 1963).

He writes about Tao, the Way, as something you can’t grasp directly, only live. Again and again he praises softness over hardness, water over rock, yielding over forcing. The famous principle of wu wei often translated as “non-action” is less about doing nothing and more about acting without strain, without ego pushing in all directions (Lao Tzu, trans. Mitchell, 1991). It’s a very different model of strength from the Western heroic image of the lone warrior conquering the world. Lao Tzu’s hero looks suspiciously like a quiet person doing their job, taking the next step, saying little.

Men, solitude and the long night shift

As a trainee psychotherapist who also works nights, I find something deeply consoling in that. So many men I meet in therapy rooms, at desks, in corridors are living lives that are structurally quite similar: long hours, quiet responsibility, not a lot of applause. Pollack writes about the “male code” that asks men to be strong, stoic and self-reliant, often at great emotional cost (Pollack, 1998). Courtenay notes that men are less likely to seek help, even when they are struggling, because doing so can feel like breaking that code (Courtenay, 2000).

When I come home after a night shift, carrying the weight of other people’s stories and the practical worries of my own family, Lao Tzu’s line about “teaching without words, performing without actions” hits differently (Lao Tzu, trans. Lau, 1963). Most of what I do for the people I love is not dramatic. It looks like turning up on time, staying awake when I’m tired, sending money, making sure there is food, holding boundaries. It’s not Instagram-worthy; it’s closer to what Jung called “the small tasks of every day” that actually shape a life (Jung, 1964).

In that sense, many working men are already living something like wu wei. They are doing what needs to be done, often invisibly, so that the rest of the system doesn’t collapse. No speeches. No heroic soundtrack. Just soft perseverance against hard circumstances.

Softness isn’t weakness

One of the paradoxes I’m still learning both as a therapist-in-training and as a man is that softness is not the opposite of strength; it is a different kind of strength. Rogers famously wrote that when a person feels deeply accepted, they can begin to change (Rogers, 1961). That acceptance is not dramatic either. It’s quiet, attentive, non-competitive. It feels very close to Lao Tzu’s “way of the sage… to act, but not to compete.”

In practice, this means that in the therapy room, and in ordinary life, I’m trying to move away from the fantasy of fixing everything through sheer force more arguments, more cleverness, more control. Instead I am experimenting with being a bit more like water: staying in contact, finding the available path, trusting that persistence sometimes does more than aggression. On some nights this looks wise and serene. On other nights it looks like a man in a high-vis jacket drinking lukewarm tea and reminding himself not to send that passive-aggressive email.

A year of unfinished archetypes

From a Jungian angle, this past year has been a lesson in how archetypal patterns can start to run the show if we are not paying attention. Jung described archetypes as deep, shared patterns of experience Hero, Lover, Outcast, Sage that we unconsciously try to live out (Jung, 1969). When those patterns don’t get lived in a reflective way, they tend to leak into our relationships, workplaces and fantasies.

I’ve seen that in myself: moments when the “rescuer” archetype wants to take over, when the “hero” wants a dramatic storyline instead of a quiet life, when old longings look for a stage. Training has helped me notice those impulses without blindly obeying them. Hillman suggests that our “daimon” our inner guiding pattern doesn’t always want us to be spectacular; it wants us to be true to our character (Hillman, 1996). Sometimes that means allowing a mythic script to not complete itself, to let a story stay unfinished so that real lives don’t get damaged trying to live out an inner drama.

Tongue-in-cheek wisdom for working men

I think this is one reason I love that Lao Tzu quote sitting on my desk, in all its slightly ridiculous glory. It’s profound, yes. It’s also printed under the word “Lunch,” which keeps me suitably grounded. The image that stays with me is not of a levitating sage, but of an ordinary man on a very human break, chewing a sandwich and silently repeating:

“The softest thing in the world overcomes the hardest thing in the world.”

translated into something like: You don’t have to win every argument tonight. Just keep turning up, keep your integrity, and let time do some of the heavy lifting.

This is a small shout-out to men who are doing exactly that:

men working nights, driving buses, cleaning offices, sitting at desks, fixing boilers, supporting families, paying bills, looking after parents, trying to be decent fathers, partners, brothers and sons. Many of them will never quote Lao Tzu. Some of them might roll their eyes at the idea of archetypes. But in their daily persistence, their small acts of care and restraint, they are living something very close to what the Taoists call the Way.

Walking into the new year

As I step into the new year, my resolutions are embarrassingly simple. I want to continue my training, keep my marriage and family at the centre, and do my work both therapeutic and practical with a little more softness and a little less frantic striving. I want to remember that boundaries and kindness are not opposites. And I want to hold on to the quiet faith that simply staying present, night after night, can itself be a form of wisdom.

If Lao Tzu were somehow sitting at my desk, looking at the monitors , I imagine he might smile and say that the Way doesn’t always look mystical. Sometimes it looks like a man on a long shift, acting but not competing, soft but not weak, doing his best to support the people he loves. And honestly, for this year, that feels like enough.

References

Courtenay, W.H. (2000) ‘Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health’, Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), pp. 1385-1401.

Hillman, J. (1996) The Soul’s Code: In Search of Character and Calling. New York: Random House.

Jung, C.G. (1964) Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books.

Jung, C.G. (1969) The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. 2nd edn. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lao Tzu (1963) Tao Te Ching. Translated by D.C. Lau. London: Penguin.

Lao Tzu (1991) Tao Te Ching: A New English Version. Translated by S. Mitchell. New York: HarperCollins.

Pollack, W. (1998) Real Boys: Rescuing Our Sons from the Myths of Boyhood. New York: Henry Holt.

Rogers, C.R. (1961) On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. London: Constable.